UCLA Medical School’s ‘guest artist’ is helping to teach doctors about disease

From the Huffington Post

Article by Priscilla Frank

Ted Meyer is the guest artist at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. If you weren’t aware that medical schools had guest artists, you’re not alone. But this initiative is very real, aiming to teach doctors about illness through the practice of art.

Yes, Meyer’s work brings artists together to help educate future physicians and epidemiologists on the more human aspects of disease. “The artists use their work to tell a story,” Los Angeles-based Meyer told The Huffington Post. “It helps the doctors look at people as more than something to cure.”

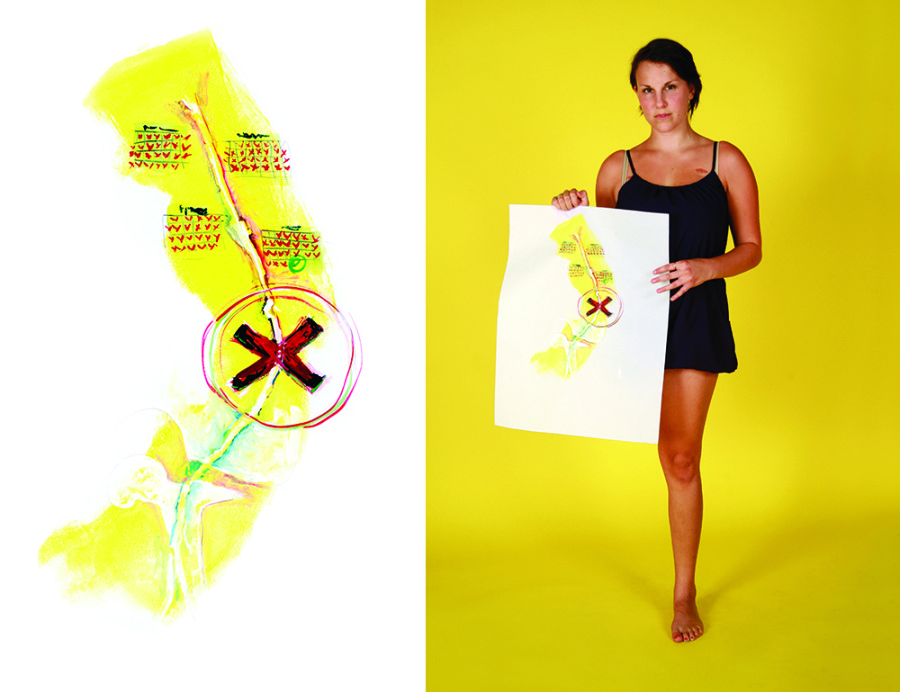

Daphne Hill, Avian Flu: “Daphne does work about germs and her fears of them sickening herself and her children. Her talk was interesting as she explained how her fears developed and how doctors might talk with someone like her who has already been checking the Internet and read the possible worst case scenarios.”

Meyer began his stay at the medical school in 2010, though the foundation of his ongoing project began much earlier — in fact, his inspiration dates back to his birth. “I was born with a very rare genetic condition,” said Meyer, who grew up with Gaucher’s disease, a disorder in which fatty substances accumulate in cells and organs. “There was no treatment for it. Starting at about age 6 I was in and out of the hospital all the time. I grew up thinking maybe I’d make it to thirty, maybe not.” Among other things, manifestations of the illness include bruising, fatigue, anemia and skeletal disorders.

During his time in the hospital, Meyer turned to art as a means of expression, release and inner healing. Creating imagery filled with skeletal bodies contorted in pain, Meyer’s resulting series was titled “Structural Abnormalities.” He often made use of the materials around him, incorporating bandages and IVs into his images, all revolving around the idea of, in Meyer’s words, “being in a body that didn’t work particularly well.”

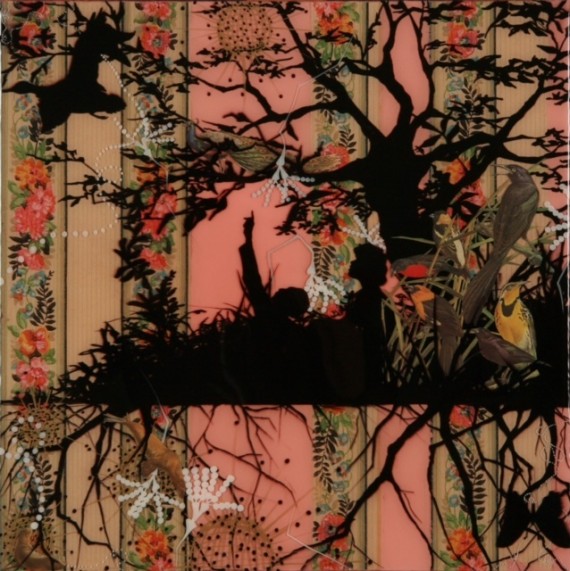

Damienne Merlina, Bandaid

And then, something unexpected happened. Meyer’s health began to improve. “I really hit a point where, thanks to Western technology, there was a new treatment. Almost all of my symptoms disappeared,” he said. “I had my hip replaced so I could walk normally.” Although undoubtedly a miracle in terms of his life and wellbeing, the sudden shift left Meyer directionless as an artist.

After a period of uncertainty, Meyer resolved to shift his artistic perspective entirely. While still focused on the body, his work shifted from its “singular and isolated” mode to one more “happy and sexual.” More importantly, instead of sharing his own story, he began inviting others to share theirs.

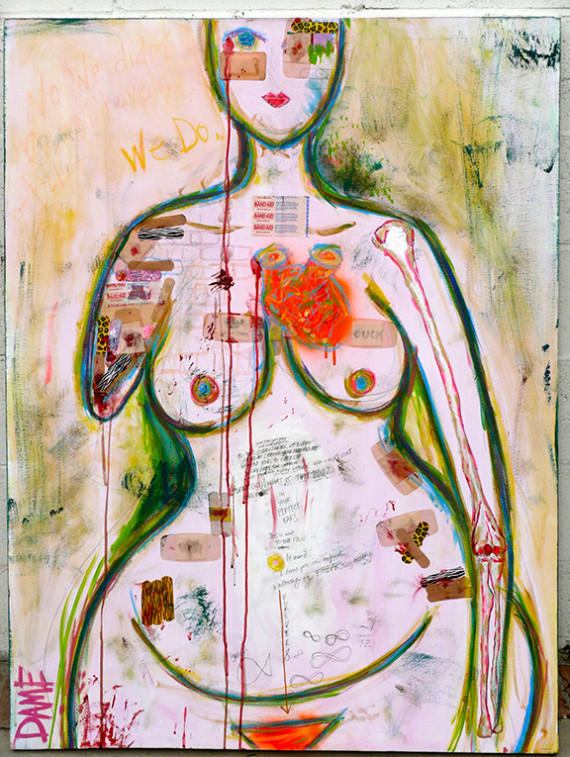

For this series, which Meyer dubbed “Scarred for Life,” he applies block-print ink to human scars and the skin surrounding them. He then proceeds to press paper to skin, and subsequently accents the images with paint and pencil, turning physical remnants of suffering into inimitable splashes of color and line. Although the project center around scars, the art is less about suffering and more about survival. “I make these prints that look like Rothkos — color field prints,” he said. “I don’t want [to emphasize] the shock value of, ‘Oh, look how disfigured they look.’ For me, it’s a story more like mine: let’s make the best out of this that we can from this point forward.”

Ted Meyer, Breast Cancer-Mastectomy

Meyer explained the intense reactions he received in response to the works, which toured everywhere from the United Nations to the Pasadena Armory; reactions of an intensity he never experienced when painting. “People would come look at my work and just sort of break down crying,” he said. “Others came up to me and said, ‘Look at my scar, let me tell you about my scar.'” He was receiving emails twice a week from people all around the world, all wanting to share their personal scar story.

This gave Meyer an idea. With so many people grappling with illness and using art as an outlet, perhaps their creative efforts could serve as a means of unorthodox education as well. “It became very apparent to me that all these people who do work about their illnesses, really have a lot to say,” Meyer said. “Maybe they could teach something to medical professionals. There has been art therapy designed to help patients, but I thought maybe there is something to teach the doctors here. Perhaps they can look at patients’ artworks and see something beyond the clinical. It’s not just ‘oh, they have multiple sclerosis’ or ‘it’s a broken neck.’ In a way, it’s like art therapy for doctors.”

As a result, for the past five years, Meyer has served as a guest artist at the UCLA’s medical school, a position he carved out and created for himself, curating artist talks and exhibitions that serve to educate the medical staff. In particular, Meyer’s programming is designed for first and second year medical students, most of whom have not yet had an opportunity to work with patients in person. To provide future doctors with more tangible understanding of living with certain afflictions, artists speak about their condition, their artworks, and the relationship between the two.

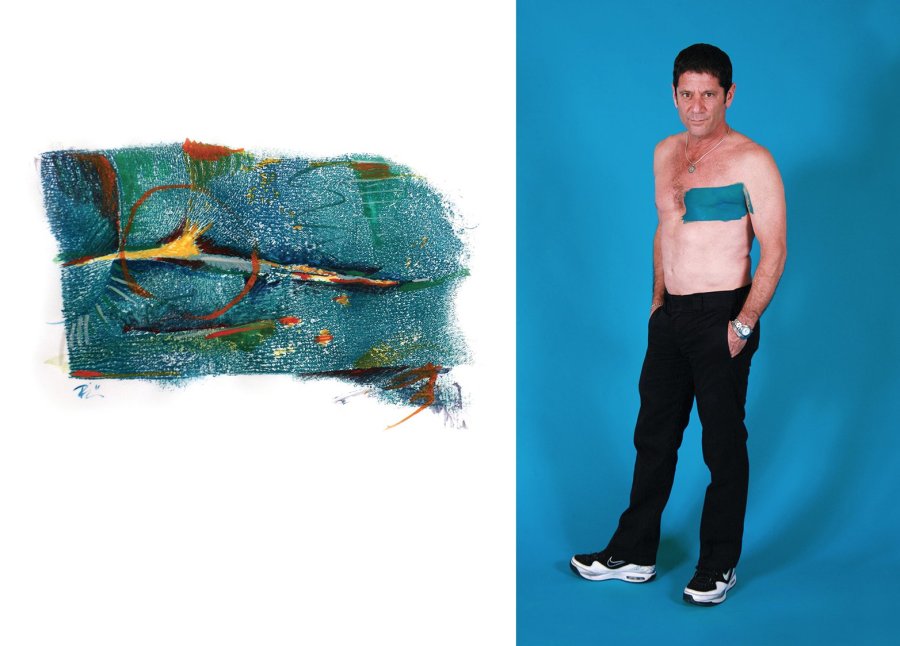

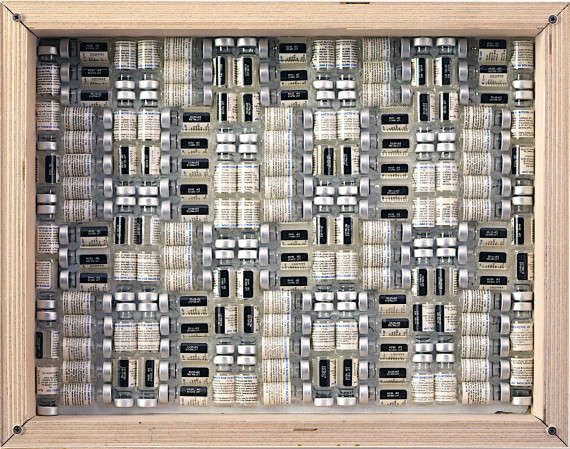

Susan Trachman, Order #2 Susan has MS and does work about organization and control as she has less control over her body. He media is all the old medical supplies used in her treatment

Mainly, his position entails recruiting and curating a network of artists exploring issues of illness and identity, inviting them to show their work and tell their stories. The conditions represented are as diverse as the artistic media explored. “There is a woman Susan who has multiple sclerosis,” Meyer said, “and for 25 years she’s been keeping all the bottles she’s used — all the saline and everything — she takes them and she organizes them in patterns. She explained to the medical students that when you have MS you have absolutely no control over your body. You can’t predict your own movements. But by organizing these bottles, she had found one area she could control.”

Meyer’s program caters to doctors who, though familiar with all the technicalities of medical proceedings, aren’t as well versed in the human aspects of the profession. “There are a number of doctors who are very smart but when they get on the floor and have to start dealing with patients they break down,” he said. Especially today, many doctors don’t have the proper time to truly get to know their patients, the ways their various struggles have shaped the people they are.

“There was another woman who had a headache for around four years. During that period she had lost her ability to name things, she couldn’t remember the nouns. When she finally got rid of her migraine, she went back and photographed all the things she couldn’t remember. For someone to tell their story to first year med students — it’s not just, ‘Oh, you have a headache, what medicine should I give you?’ It’s a new way to understand the life process of living with an illness.”

Meyer’s unorthodox merging of art and medicine proves that art therapy isn’t only helpful for patients, but doctors as well. “It’s a new way to connect,” Meyer said. “We are making positive things out of these horrible situations.”

Image above: Ted Meyer, Scarred for Life: Meyer uses block-print ink to transform human scars into vibrant colorful abstractions in his “Scarred for Life” series, inviting others to share the physical remnants of their survival stories.

Find more images of art works online.