The Brooks Center for the Performing Arts turns 20

“I’d venture to say we have 2,000 students coming through the building every week,” Lillian “Mickey” Harder estimates. Harder, who is in her 18th year as director of the Brooks Center for the Performing Arts at Clemson University, marvels over how busy the facility is on a daily basis. It was not always like this.

Two decades have passed since the dedication of the Brooks Center in April of 1994. In that time, the Center has played host to hundreds of student and professional productions. It was the birthplace of the production studies in performing arts major, the only one of its kind in America, which has graduated roughly 140 students in 12 years of existence. On Thursday, February 6 at 8 p.m., it will welcome hundreds of students, alumni, and patrons in an anniversary celebration of the value the Center has brought to the community.

But the story of the Brooks Center is much richer than a handful of numbers. That story began decades before ground was broken.

The performing arts have always been a part of Clemson. In the nearly 80 -year span between 1893 and 1972, the Men’s Glee and Cadet Corp formed, the College Concert Series started, the first full-time music faculty were hired, students founded the Clemson Players, and a chamber music series began. Littlejohn Coliseum, Tillman Auditorium, Daniel Hall, and the Clemson Field House (now known as Fike Recreation Center) all took turns hosting these myriad performers. In addition to resident student ensembles, legends such as Itzhak Perlman and Dizzy Gillespie graced the campus of the modest agricultural institution. Harder remembers Perlman’s concert vividly. At the time a piano instructor at the University, Harder was a page-turner for Perlman’s collaborative pianist the night he gave his concert in Littlejohn Coliseum. The stage, which consisted of a make-shift platform at the center of the coliseum floor, was accessible only by a tall flight of stairs. Harder remembers holding Perlman’s Stradivarius violin for him while he took his bows between pieces. The acoustics, she recalls, left a lot to be desired. It was no doubt better than orchestra concerts at the Field House, however, where quiet moments in a piece were interrupted by the sounds of radiators letting off steam.

World-class musicians clambering over precarious platforms and noisy heating devices were not ideal performance conditions. Nor was the set-up in Daniel Hall, a building on campus that was and still is home to English classes. Though Daniel boasted an auditorium (then used for concerts; now a lecture hall) and an annex (then used for Clemson Players productions; now a lab for building rockets), the spaces were not conducive to full-scale concerts and theatrical productions. “I would greet people and pass out programs in the lobby, then go outside, around the building, and back inside to turn off the lights in the theatre,” Harder recalls of the auditorium. “Then I’d go back outside to take my seat.” That was nothing compared to how Harder says the piano had to get to the stage. “My piano studio was across the hall from the back of the auditorium. We would open the double doors of the studio, roll the piano down the hall and to the backdoor of the auditorium.” From there, a three-foot drop awaited the instrument from¬ the hallway to the stage, calling for a dozen facility workers to ease it onto the lower level. After the concert, same story… only lifting instead of lowering. It was a production inside of a production.

David Hartmann, current chair of the Department of Performing Arts, came to Clemson in 1990 as the scenic designer and production manager for the performing arts department. He vividly recalls the challenges inherent in producing student plays in the annex. “We didn’t have a catwalk above the stage,” Hartmann says, “so, to hang lights, you had to go up on a ladder, hang the light, go back down, move the ladder a few feet, climb up, hang the light, and repeat.” Clifton “Chip” Egan, former chair of the Department of Performing Arts, came to Clemson in 1976 as the department’s first designer and technical director. His remembrances are similar. “As the designer of nearly every set and lighting design for many years, I always felt like I was solving the theatre space rather than the play,” he says. But, ironically, this sometimes worked in favor of the performances. “Our production values were very high, considering our limitations. In fact, the limitations drove some amazing creativity.”

The production aspects themselves were not the only challenges. Daily logistical problems plagued the department. The performing arts faculty was not nearly as large as it is now, so Hartmann was in charge of teaching all aspects of technical theatre, from costumes to lights to scene design. His office, along with the rest of the theatre faculty, was located in Daniel Hall. It quadrupled as his classroom, another faculty member’s office, and that instructor’s classroom. With the exception of Harder, music faculty were located just across the sidewalk in the adjoining building called Strode Tower. Almost inconceivable in 2013, the two departments shared one printer, and it was on the seventh floor of Strode. Both Hartmann and Harder made the trek across the sidewalk and up the stairs each time a document was printed. Nothing, it seemed, was easy.

In 1976, the year Egan arrived, a petition for a performing arts center on campus was begun by B.J. Koonce and Susan Smith, members of the Clemson Players. They garnered over 4,000 names, which, at the time, was more than half of the student body. Though it did not lead to an immediate groundbreaking, it was not in vain. Egan says “[Koonce and Smith] clearly made an impression, because I came to Clemson in part because the administration was talking about building a performing arts center. Eighteen years later, it finally happened.”

At the same time that pianos were being hefted about and stairs climbed, the wheels were turning in a positive direction toward a true performing arts space. “I credit Bob Waller, dean of the College of Liberal Arts during the 1980s and early 1990s” for tirelessly advocating to the administration, Egan says. “His decision to create the department of performing arts in 1986 by merging music with theatre strengthened the case enormously.” Dean Waller then appointed Richard Nichols, “a national figure in theatre education,” as the inaugural chair of the new department. Egan says Nichols was instrumental in getting the project off the ground and made it possible for things to come.

Enter Robert Howell Brooks, who grew up in Loris, South Carolina, a rural community where he worked on the family farm during his youth. A man from modest means, he graduated Clemson in 1960 with a degree in dairy science by way of the W.B. Camp scholarship. Brooks made the decision early to one day repay the kindness offered to him and give back to Clemson.

Seven years after graduating Clemson, Brooks created the first non-dairy creamer with his first company, Eastern Foods. The success of this product led him to take on even greater challenges with the company that would come to be known as Naturally Fresh. He eventually purchased the Hooters of America restaurant chain and pursued other successful ventures. The young man who grew up with so little now had so much to give.

So when the W.B. Camp family made the first move in donating $1 million to the as-yet-unnamed arts center, it seemed natural that Robert Brooks followed. Much like Brooks, Wofford Benjamin Camp was a self-made man. Graduating in 1916 from Clemson, he became well known as a successful agricultural developer in California. His establishment of the scholarship was obviously an attempt to pay forward his good fortune. Brooks wanted a chance to make good on his vow to do the same. Egan recalls then-University President Max Lennon working with Brooks to secure the $2.5 million gift for the building that would become the Brooks Center. Dreams were becoming reality.

“The decision to have the Brooks Center designed through an international competition was a Clemson first,” Egan says, “and Jim Barker, dean of the College of Architecture at the time, was an instrumental member of the competition jury.” The Brooks Center’s physical design was heavily influenced by the performing arts department itself, with members of the administration making major decisions in its planning.

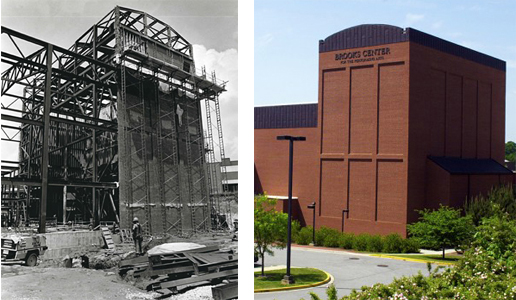

With the blueprints complete, ground was broken on the 87,000-square-foot facility in 1991. A period of heavy rain delayed the opening by a year, though that was nothing compared to the previous wait of 15 years. The Brooks Center opened in 1994 with Bruce Cook as its director and Egan as the chair of the Department of Performing Arts. Festivities greeted its opening. “We did everything on a shoestring budget,” Harder explains. She herself baked roughly 800 tea cookies for the opening reception. Community members excited about the prospect of an arts center attended en masse. The Greenville Symphony performed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The original 4,000-name petition was “re-presented” to the Board of Trustees. “It was very much a celebratory time,” Harder says. All around, it was a grand opening for a grand building.

Finally, Clemson University had its state-of-the-art performing arts facility.

“Every day that I come to the Brooks Center, I feel like Cinderella. And both shoes fit,” Harder says from her office, the window overlooking the Center’s courtyard. There is a printer right outside, not nearly as difficult to access as the seventh-floor machine of years ago. Next door, Hartmann’s office is just that: an office. On the floor below, practice rooms hum with the sounds of instruments. The theatres, too, are busy with students painting scenery and perching on the catwalk, hanging lights without a ladder.

In the arts, a piece of music or theatre usually starts with an idea, a brief glimmer of something that visits in the middle of the night. No matter how magnificent the end product, it all starts with a single strike of inspiration. Brook’s gift allows so many to wake up in the middle of the night from a dream with a spark of inspiration, knowing that, when morning comes, they will have a laboratory in which to experiment, a canvas on which to paint, and a place to come where they can say, “Ah. I’m home.”

* * * *

Special thanks to Lillian U. Harder, David Hartmann, and Clifton “Chip” Egan for their reflections.

Tickets for the 20th Anniversary Celebration on Thursday, February 6 at 8 p.m. are $35 adults and $10 students. They may be purchased through the box office, which is open Monday – Friday, 1 – 5 pm. The box office is available by phone at (864) 654-7787 or online at www.clemson.edu/brooks.

Thomas Hudgins is director of marketing and communications for the Brooks Center for the Performing Arts.