Remembering Pat Conroy

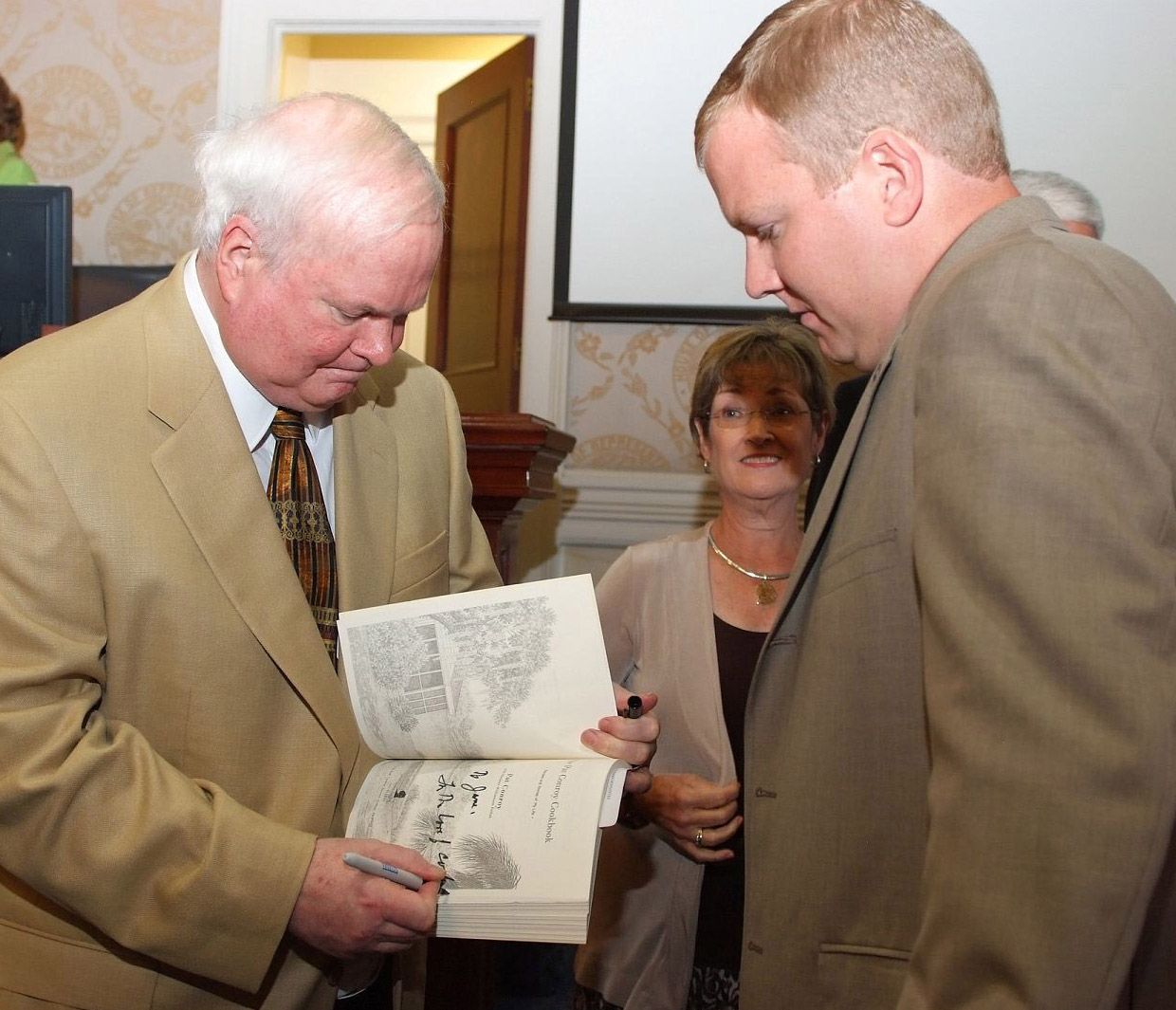

Image: Pat Conroy received the Elizabeth O’Neill Verner Governor’s Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2010. Here he autographs a book for a fan prior to the awards ceremony.

Find additional tributes to Pat Conroy on the Island Packet website.

From the Island Packet

Article by David Lauderdale

Pat Conroy, Arts Commissioner Bud Ferillo and artist Jonathan Green at the 2010 Verner Awards presentation. Conroy and Green received awards for Lifetime Achievement

Pat Conroy, who arrived in Beaufort as a teenage Marine brat and found both a home and palette for his best-selling novels, died Friday at his home on Battery Creek.

“The water is wide but he has now crossed over,” said his wife, Cassandra King, through a family friend.

Conroy, 70, was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer only four weeks ago. When he announced it Feb. 15 on Facebook, he said, “I intend to fight it hard.”

He died at 7:43 p.m., surrounded by loved ones and family.

Stomach pain was at first thought to be pancreatitis. But further testing confirmed shortly before the public announcement that it was pancreatic cancer, which spread rapidly.

His lyrical novels painted harsh pictures of inadequate schools, an abusive father and South Carolina’s military college, The Citadel. He tackled threats to the Lowcountry environment with equal vigor. But he loved each of his subjects, and the town he adopted after 23 moves in 16 years loved him back.

Beaufort historian Lawrence S. Rowland said Conroy put Beaufort on a national stage through books like “Prince of Tides” and “The Great Santini.” And those novels brought Hollywood to town, and the stars would return for other blockbusters like “Forrest Gump” and “The Big Chill.”

“I can’t imagine anything other than World War II that promoted Beaufort any more than what Pat did,” Rowland said. “The value of Pat’s publicity — to put Beaufort on the silver screen and advertise it, and the millions of fans who read his every word — is hard to measure.

“I know there’s controversy, and I think he’s entitled to any opinion he chooses, but the amount of good he’s done is exceptional. It’s a huge economic boon to this town and he’s the kind of guy we ought to raise a statue for.”

Beaufort Mayor and close friend Billy Keyserling said, “His impact has really been to the region and opening up eyes, concurrently with the growth of the greater Lowcountry. He was a part of turning the eyes to this part of the world.”Jonathan Haupt, director of the University of South Carolina Press, said, “It’s a sad, sad day for South Carolina and for literature.”

Conroy appeared to feel fine when the University of South Carolina Beaufort hosted the “Pat Conroy at 70” festival organized by Haupt in late October. Numerous writers, friends and family members came to celebrate a life that was on an uptick.

Conroy had never been busier, more productive, or more public. In addition to his own writing, he was promoting a stable of other writers in the Story River Books imprint he edited for the University of South Carolina Press.

Conroy had been on a health kick for four years. He said that’s when he nearly died of his own bad habits, so he quit drinking, hired a nutritionist, joined the YMCA, lost weight, andlast year opened the Mina & Conroy Fitness Studio in Port Royal with his personal trainer.

“There is nothing on my resume that indicates I’ll be successful in this unusual endeavor,” he wrote on his web page. “But I’m doing it because there are four or five books I’d like to write before I meet with Jesus of Nazareth — as my mother promised me — on the day of my untimely death, or reconcile myself to a long stretch of nothingness as my non-believing friends insist.”

Home at last

Alexia Jones Helsley says she was Conroy’s first editor.

The daughter of the Baptist preacher in town was editor of the Tidal Wave newspaper at Beaufort High School, where Conroy first latched onto the Lowcountry in the remarkable class of 1963.

“He took a track meet and turned it into a race between good and the Devil,” Helsley said. “It was hilarious.”

Another time, principal Bill Dufford asked Conroy as president of the senior class to address the girls before a powder puff football game.

“He took a napkin from the cafeteria and wrote this little poem on it and got up and read it,” Helsley said. “We thought he was so talented, but we had no idea how talented he was.”

Conroy was a basketball star and Best All Around in a class that had six National Merit Finalists, and included Daisy Youngblood, a sculptor who won a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant”; Daun van Ee, editor of the papers of Dwight D. Eisenhower at the Library of Congress; and Julie Zachowski, retired director of the Beaufort County library system. Helsley is an archivist who has written a history of Beaufort. Conroy is among three members of the class inducted into the school’s hall of fame.

Conroy wrote often of inspiring teachers there, like Millen Ellis and novelist Ann Head, but especially Eugene Norris.

“He taught me to value the old, to sharpen my eye for the most intricate detail, and to strengthen all the appetites upon which beauty itself fed,” Conroy would later write. “In the end, Gene Norris handed me the key to my first hometown and made it feel like the most sublime gift.”

A new life

Conroy returned to Beaufort High as a teacher after graduating from The Citadel, but a much different school on Daufuskie Island cast the die for his life.

“The Water is Wide” — and the movie version “Conrack” — described Conroy’s year battling authorities to stretch the stunningly limited opportunities and achievement of students on a remote island.

A number of Beaufort women, including Harriet Keyserling, typed portions of the manuscript written in longhand on a legal pad in a breathless dash to get it to his publisher on time. It was published in 1972, launching a new career.

When Conroy was inducted into Penn Center’s 1862 Circle in 2011, he was cited for helping show the world the South’s unequal public education for blacks and whites. He told the crowd that despite the abuse he took for saying it, he thought he got it right.

It set in motion a career of writing what others would not dare write. It cost him relationships at his alma mater and in his family.

In 1976, he published the look inside his family of seven children, a beautiful mother and a boorish fighter pilot. In “The Great Santini” he told of his father. Col. Don Conroy was a heroic Marine, but he beat his wife and children. To the outside world, the book was a smash hit. The movie was filmed in Beaufort.

Conroy was banned from campus after the 1980 book about The Citadel, “Lords of Discipline.”

As other books chronicled the rough edges of a life like his own, with two divorces, suicidal thoughts and psychiatric issues, Conroy’s smooth writing and brutal honesty made him a regular on the New York Times best-seller list. Other titles include “South of Broad” set in Charleston, “The Pat Conroy Cookbook: Recipes of My Life” and “My Reading Life.” His books were sprinkled with local favorites from Dr. Herbert Keyserling to Snowball the albino dolphin.

He later found peace with The Citadel, and wrote another book about his experience there, “My Losing Season.”

And he found a happy marriage to novelist Cassandra King. They have lived on the banks of Battery Creek in Beaufort, which they both can see from their writing rooms, and where he could smell the pluff mud late in the day while enjoying a cigar and a Lowcountry sunset only he could put in words.

He had lived in Atlanta, Italy and San Francisco. But in 1993, he came home for good.

Conroy also found peace with his father, the Great Santini. That was chronicled in the 2013 book drenched with the people and places of Beaufort, “The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son.”

“If my father knew how many tears his children had shed since his death,” Conroy wrote in his father’s eulogy, “he would be mortally ashamed of us all and begin yelling that he should’ve been tougher on us all, knocked us into better shape — that he certainly didn’t mean to raise a passel of kids so weak and tacky they would cry at his death.”

‘OK to be in therapy’

As Conroy’s former therapist, no one may know him quite like Marion O’Neill, a psychiatrist and the inspiration for the psychiatrist in Conroy’s 1986 book, “Prince of Tides.”

The best-selling novel was later turned in a 1991 movie with Barbra Streisand playing the lead role.

O’Neill treated Conroy during two periods of his life — first in Georgia in the 1970s and then in the 1980s at her Hilton Head Island practice while Conroy was working on another best-selling novel, “Beach Music.”

“He’s always made the statement that I saved his life twice,” said O’Neill, 86, who retired in 2010 when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. “It means that I kept him from going off the rails.”

O’Neill, who now lives in her hometown of Norwell, Mass., won’t dish on her therapy sessions with Conroy.

Rather, her focus is on the acceptance that he brought to psychological treatment.

“He made it OK to be in therapy and to say you had some mental problems,” O’Neill said. “That was his biggest contribution because people always thought they had to hide it and it was a secret … It was particularly true for men.”

While the two friends haven’t talked in a few years, O’Neill still chuckles when she remembers Conroy’s wicked sense of humor.

Following the release of “Prince of Tides,” many wondered if Conroy and O’Neill had had a romantic relationship like the two characters in the book.

“He was often asked if he had slept with his psychiatrist. And he would say, ‘No, only because she wouldn’t let me,’ ” O’Neill said. “He always had a great sense of humor.”

Civic involvement

Conroy used his pen occasionally as a local activist.

In 2006, when the city sought to annex rural land along U.S. 21 north of town that could open development to 16,000 residences and 40,000 people, Conroy fired back.

“For the life of me, I cannot understand why Mayor Bill Rauch and most of the members of the City Council seem to loathe the exquisite and endangered town of Beaufort,” he wrote in The Beaufort Gazette.

“I’ve made a career out of praising this town’s irreplaceable beauty and the incomparable sea islands that form the archipelago that makes Beaufort County the loveliest spot on Earth to me. A man once told me while we watched a full tide coming up on Fripp Island accompanied by a full moon, ‘The only thing I worry about heaven is that it won’t be as pretty as this.’ That was 10 years ago. Now, my greatest worry is that developers are going to figure out a way to pave the ocean.”

In the same piece, Conroy was open about Beaufort’s influence on his life:

“Am I anti-business and anti-progress? I think somewhat. But I believe I have brought more tourists and outsiders to visit these islands than anyone I can think of and have praised their beauty all over the world in books you can open up and smell the great salt marshes of our rivers and creeks. I have written more about Beaufort County than anyone who has ever lived here, and I believe with all my heart that I love this place as much as anyone who has ever crossed the Combahee River.”

In another op-ed on the same issue, Conroy used his passion to stir others to action:

“I owe my writing life to this spot of earth. This extraordinary geography has provided the joy of my youth and the comfort of my old age. In my last breath, I believe Beaufort is worth fighting for. I urge all of you to come to the last meetings. This is our homeland — the place that makes our hearts sing. It needs us to rise up in its defense. It needs us now — right now.”

More recently, he lent his name to a fundraising drive for athletic facilities at the new John Paul II Catholic School in Okatie.

He has aided fundraisers for USCB and the Beaufort County Open Land Trust.

In 2014, the Beaufort Regional Chamber of Commerce created an award in his name.

When he received the first Pat Conroy Palmetto Achievement Award, Conroy joked that he must have outlived his enemies.

And he told the audience:

“Two questions a military brat can never answer is ‘where are you from’ and ‘where are you going to be buried,’ I can now answer that. I am from Beaufort. And this is where I’m going to be buried.”