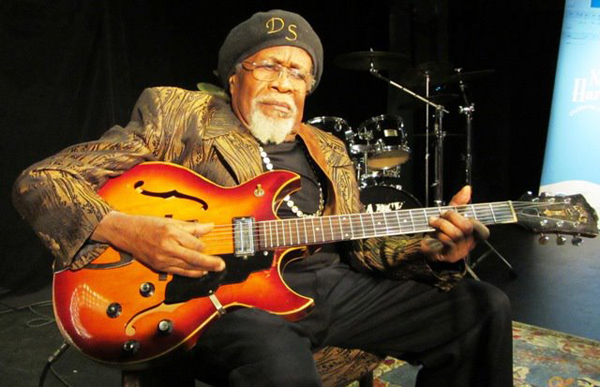

“I just want my story told” — new biography delves into life of blues legend Drink Small

Gail Wilson-Giarratano was awarded a One-Time Project grant of $3,000 to help publish “Drink Small: The Life & Music of South Carolina’s Blues Doctor.” Small will appear with Wilson-Giarratano at a book signing at Uptown Gifts, 1204 Main St., Columbia, Thursday, Dec. 11 from 11:30 a.m. – 2 p.m. Small received a Jean Laney Harris Folk Heritage Award in 1990. Find out more about Small on his Facebook page.

From The State:

A new biography of one of South Carolina’s most-recognized bluesmen paints a portrait of an irrepressible showman who spent a lifetime “boogalooin’ on Saturday night and hallalujehin’ in church on Sunday.”

But the story of Drink Small by Gail Wilson-Giarratano does more: It delves into the wellspring of Small’s signature Piedmont blues, from a horrifying boyhood accident in the cotton fields of Lee County to the baby thrust into his arms by a departing woman and the dimming of his eyesight in his later years.

Blues and gospel flowed in and out of Small with abandon, no matter whether he was playing music festivals, touring with gospel groups like the Spiritualaires, or printing his own fliers to jumpstart a flagging career, she writes.

“It was always highs and lows,” said Wilson-Giarratano, who will sign books Thursday at Uptown Gifts on Columbia’s Main Street. “He has always said everybody gets the blues, but not everybody has the blues.”

In many ways, Wilson-Giarratano says, the story of Drink Small is the story of South Carolina, tortured and contradictory, mysterious and luminous.

Always, always the geography of South Carolina, its cotton fields and wooden shacks, juke joints and houses of worship, its people, black and white, formed the soul of the man known as the “Blues Doctor.” He never wanted to leave, which in the end stymied his attempts to make it nationally and internationally.

“Drink has been part of so many significant moments in people’s lives in South Carolina,” Wilson-Giarratano said. He played on college campuses, in churches and dance halls. There were gigs at blues festivals, beach pavilions and weddings.

But in the end, she wonders: “How much do we know about his life?”

‘I just want my story told’

Wilson-Giarratano clearly loves Small, whom she met in the 1980s when she worked for the Lancaster Arts Council and ferried Small to various arts functions. After a hiatus working in New York, Wilson-Giarratano renewed her acquaintance with Small when she returned to South Carolina and began heading up the nonprofit City Year in Columbia.

Shortly after his 80th birthday celebration Jan. 27, 2013, at the 145 Club in Winnsboro – a party where the blues legend celebrated the sayings he calls “Drinkisms” – Small and his wife, Adrina, asked Wilson-Giarratano to write his story. “I just want my story told. I ain’t got much time,” he told her.

The History Press in Charleston published the 175-page book. A Kickstarter campaign, and grants from the S.C. Arts Commission and the Tradesman Brewing Co. of Charleston cleared the path to the book’s publication. Wilson-Giarratano had to purchase the first 500 books but she has signed over royalties to Small.

The book already is getting some attention. The German blues online publication Wasswe-Prawda did a feature in hopes of luring the 82-year-old to come to Europe to tour.

Small, who got on an airplane once many years ago for a European tour, isn’t about to do that again – he’s deathly afraid of flying – although he said Monday he is excited about the book launch.

“Just don’t think of me as a blues and gospel man – they don’t have Drinkisms,” he said, speaking of his repertoire of life aphorisms.

“I want everyone to read this book,” he said. “I guaranteed if you read this book, you are going to get hooked. It was one of those slam-jams. There is no other Drink Small. I’m an original.”

‘So sad make you wanna cry’

The story of the Bishopville native with the unusual name began in 1933 when he was born into a sharecropping family. Like thousands of other Southern children, he expected to live and work in the fields, but one moment on the old Stuckey plantation changed his path.

The 8-year-old Drink was riding a mule-drawn wagon, when the wagon lurched into a trench, tossing Drink and cotton bales off the side. As his uncle Louis slapped the reins to get the mule moving again, the young Drink was caught under the moving wheel and suffered a severe injury to his back.

Doctors and hospitals were out of reach of the Small family but a midwife rushed to the shack where Drink lay. Shortly after, she directed Drink’s mother, Alice “Missy” Small, to prepare a mud-clay mixture which she applied to Drink’s back and then wrapped him in thin strips of flannel and wool. It hardened into a makeshift body cast, which he wore for weeks. When the cast came off, it was clear he would never pick cotton again.

Small turned that accident on its head and called it a moment of luck that turned him onto his musical path. He resisted Wilson-Giarratano’s probing into the long-ago incident.

“He said something so sad make you wanna cry,” she said. “He didn’t want to talk about it. There is just a vulnerability, an underlying level of sadness and pain.”

The most ‘unusual character’

The lyrics that Small penned through the years, and sometimes recorded, testify to the tribulations of his life as well as its joys – good food, particularly barbecue, pretty women, the thrill of the shag dance and the memories of his hometown.

When he moved to Columbia in 1955, bringing his mother Missy with him to care for her, something was always surprising him or knocking him off his feet. There were great gigs, touring with the gospel group, the Spiritualaires, with the Staple Singers and with Sam Cooke, and his work at WOIC.

But he also found himself in 1961 with a baby to support when a woman of his acquaintance told him she was having his child. A year later, the woman left the baby with Small and his mother to raise.

In 1957, Sam McCuen was a 16-year-old white high school student, managing a fledgling entertainment business with his friend Bill Otis, when he met Drink Small and began a friendship that lasts to this day.

McCuen swears Small could have made it big if he would only have been willing to leave South Carolina. But Small had done that in 1991 when he played the Finland Blues Festival and he wouldn’t do it again even though he was a sensation there.

“We begged him, we pleaded with him and we even thought about drugging him and putting him in a body bag,” McCuen recalled. “Had he played Europe he would be a millionaire today. It just breaks your heart thinking about it.”

Still, McCuen said, he wouldn’t have given anything for the friendship he has shared with Small. “He is the most unusual character you’ll ever meet in your lifetime,” McCuen said. “If you enjoy the foibles of life and the humor of living can you imagine having a friend like that?”

“His Drinkisms, his spirit and his passion are still there.”

If not fame and money, South Carolina has repaid his loyalty with awards galore, including induction into the S.C. Music and Entertainment Hall of Fame, Wilson-Giarratano notes in the book. He also received a South Carolina Folk Heritage Award from the S.C. Legislature.

“I’ve never met anybody who loves this state more,” she said.